Biothermal pursuits

Purva Joshi came for the master's program and stayed for a Ph.D.

Anna Boyle

May 7, 2019

Source: College of Engineering

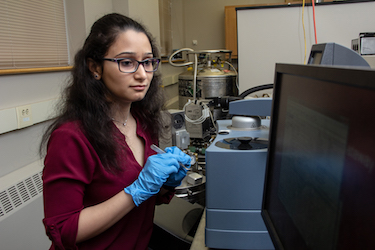

At work in the Biothermal Technology Laboratory.

Everyone takes a different path through education. Some people pinball around the country, finding and dropping schools as their interests change. Others find a school they like and stick with it. Purva Joshi is in the latter category; she happily chose Carnegie Mellon University for both her master’s and Ph.D., confident in the groundbreaking research she could do here.

Joshi received her undergraduate degree in mechanical engineering in Pune, India. She decided not to jump into the workforce, instead following her passion for research. “I realized I wanted to study more and get into the research side,” Joshi says. “I didn’t want to get into the industry right away. I needed to learn more.”

When deciding on a graduate school, Joshi looked for a place where she could explore the overlap between engineering and medicine. “As a child, the question was whether I wanted to be a doctor or an engineer,” Joshi says. “I chose engineer, but the love of medicine never left me.” While the two career paths may have been presented as exclusive, Joshi thinks that they actually have a lot in common. “At the end of the day,” she says, “they’re intersecting and complementing each other.”

Luckily, she found what she was looking for at Carnegie Mellon. “CMU allows you to do both because the programs are so interdisciplinary,” she says. She reached out to Yoed Rabin, a mechanical engineering professor whose work she admired, and he responded with enthusiasm. Her choice was made.

Only 10% of the worldwide demand for organ transplantation is being met, and 22 people die every day waiting for a transplant.

Joshi Purva, Ph.D. student, Mechanical Engineering, Carnegie Mellon University

Source: College of Engineering, Carnegie Mellon University

At the Mechanical Engineering Graduate Research Symposium.

At Carnegie Mellon, Joshi was able to enjoy a wide range of classes. “I really liked the course I did with my advisor (Rabin), called thermal design,” Joshi says. She also enjoyed her classes on artificial intelligence, machine learning, and human physiology. Outside of the classroom, Joshi got involved with various extracurricular activities, including the group Women in MechE, where she was able to benefit from a community of likeminded women.

At that point, Joshi knew that a master’s degree wasn’t enough for her; she wanted to get a Ph.D. Luckily, she didn’t have to agonize over where she should apply. “I did not apply anywhere else,” she says. “I just wanted to be here.”

Now in her second year of her Ph.D., Joshi is working on improving cryogenic preservation, i.e. the preservation of biological tissues and organs at extremely low temperatures. While this method is great for extending the shelf life of organs, it also comes with risks. The main issue is ice crystallization, which can severely harm the organs. Joshi is currently investigating the process of vitrification—cooling and warming tissues at high rates—and how it could be used to prevent such damage.

Her research could one day save lives. “Currently, the gap between organs that are needed and the organ donors is very large,” Joshi says. In fact, only 10% of the worldwide demand for organ transplantation is being met, and 22 people die every day waiting for a transplant. If cryogenic preservation is improved, organs could be transported around the world, giving patients a higher chance of receiving the life-saving organs they need.

The research is undeniably worthwhile, and Joshi wants to continue doing similar work. “Once I have my Ph.D., I would definitely like to continue with research,” Joshi says. “I am considering academic settings or research labs.”

As for other students at Carnegie Mellon, master’s and Ph.D. alike, Joshi has some advice. “You need to explore the opportunities CMU gives you,” she says. “They might not interest you at first, but you never know until you try.” She also says there’s no shame in asking for help. “Just reach out,” she says. “Everybody’s very approachable.”

“It’s such a safe environment,” she adds, a smile on her face. “It really feels like home.”

Media contact:

Lisa Kulick

lkulick@andrew.cmu.edu