Could reconfigurable metastructures be the holy grail of physical intelligence?

Kaitlyn Landram

Mar 18, 2025

It’s easy to take joint mobility for granted because, without thinking, we are able to turn the pages of a book or bend to stretch out a sore muscle. Designers don’t have the same luxury. When building a joint, be that for a robot or wrist brace, designers seek customizability across all degrees of freedom but are often restricted by their versatility to adapt to different use contexts.

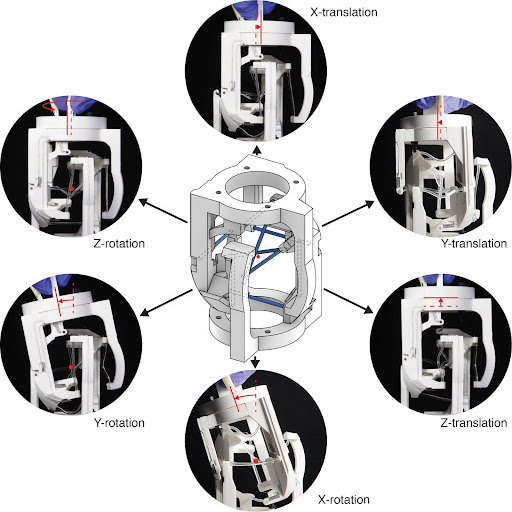

Researchers at Carnegie Mellon University have developed an algorithm to design metastructures that are reconfigurable across six degrees of freedom and allow for stiffness tunability. The algorithm can interpret the kinematic motions that are needed for multiple configurations of a device and assist designers in creating such reconfigurability. This advancement gives designers more precise control over the functionality of joints for various applications.

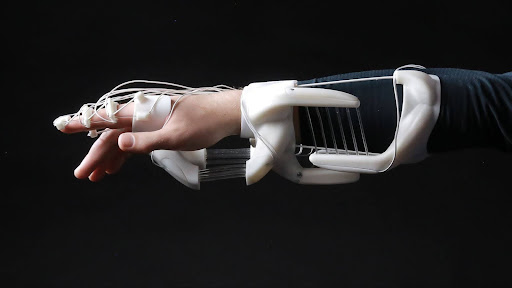

The team demonstrated the structure’s versatile capabilities via multiple wearable devices tailored for unique movement functions, body areas, and uses.

“In the case of carpal tunnel syndrome, a typical wrist brace prevents patients from exercising their joints at all times to avoid injury and promote healing. But oftentimes during rehab, patients still need to momentarily move their joints to carry out chores that were typically effortless to do. Because our structures can reconfigure to selectively lock and unlock motions, it can restrict motions to fulfill the function of a brace for the majority of the time, but selectively allow the patient to move their joint in intended ways for short periods of time. This allows patients to engage in daily activities without having to frequently take on or off the brace,” said Humphrey Yang, mechanical engineering postdoctoral researcher.

Resistive heating wires added to the 3D-printed metastructure published in Nature Communications enable the structures to reconfigure their motional degrees of freedom during use. In the future, the team believes they will have the necessary technology to additively manufacture the entire device as one piece. This would reduce production costs and allow for affordable devices with enhanced functionality.

“This is a gateway project for exciting applications,” said Dinesh K. Patel, research scientist. “Our algorithm is material agnostic, so in the future, we could look to create devices with soft, flexible materials for more comfortable wear.”

Roboticists could benefit from the structure’s ability to reconfigure joint mobility because a robot designed for multiple purposes could need varying mobilities. The ability to design joints with programmable and arbitrary reconfigurability could be a “holy grail” in creating versatile robots. For instance, as part of a home helper robot, a joint could enable a few rotational degrees of freedom to mimic a human limb. The robot could then interact with objects with human-hand capabilities. However, when interacting with soft objects or in water, the joint could reconfigure to provide more degrees of freedom as well as lower its stiffness, allowing the limb to functionally morph into a tentacle for better grasping and swimming.

Additionally, the device’s ability to reconfigure and provide various stiffnesses enables it to mimic the sensation of touching materials ranging from soft gel to metal surfaces. This could advance augmented reality for rehab and medical training.

“In this field, there hadn’t been a generalizable method to design reconfigurable, compliant kinematic structures. It was important to us to democratize them and expand their versatility for wider application,” said Yang.

“It shows how mechanisms can further augment material intelligence to achieve our ultimate vision of physically-embodied intelligent matter and machines,” said Lining Yao, one of the principal investigators supervising the project and now an assistant professor of mechanical engineering at the University of California, Berkeley.

This research was conducted in the Morphing Matter Lab, directed by Lining Yao at the University of California, Berkeley, Soft Machines Lab at CMU’s Mechanical Engineering Department, and Syracuse University.